Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the traditional owners of Australia, and pay respect to Elders past and present.

We would like to thank Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians for sharing their stories and experiences. We would like to create an environment that focuses on cultural safety, where the identities and traditions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are recognised and respected. We would like to come together to celebrate shared listening, shared knowledge and dignity for all Australians.

This website offers an opportunity for Australian healthcare professionals to learn and adapt with flexibility in their clinical practice. Through greater understanding of culture across our diverse nation, organisations can strive to optimise patient-centred care and improve health outcomes for all Australians living with bronchiectasis.

Cultural Safety Training in Physiotherapy

The Australian Physiotherapy Association has launched its Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP), through the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Committee (ATSIHC). A link for the RAP and other resources can be viewed at the bottom of this page.

With implementation of the RAP, the APA will be offering cultural safety and sensitivity training courses. Please contact your local APA office for more information.

Nurses, medical officers and allied health staff are able to access cultural safety training through local public health networks, and are encouraged to contact their professional organisation for more information.

Cultural Safety through Focus on Community

The National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) describes health in Aboriginal culture as:

“Not just the physical well-being of an individual but refers to the social, emotional and cultural wellbeing of the whole community in which each individual is able to achieve their full potential as a human being thereby bringing about the total well-being of their Community. It is a whole of life view and includes the cyclical concept of life-death-life” (NACCHO, 2011).

In order to provide culturally safe and sensitive care, health professionals need to appreciate the traditions and expectations of their local community. It is recommended that healthcare providers liaise with Aboriginal Health staff, visit their local cultural centre, complete cultural safety training and view recommended resources to ensure that a positive contribution is made to the social, emotional and cultural wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healthcare Professionals

There are various roles across acute and community care settings for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healthcare Professionals. These include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Liaison Officers, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healthcare Practitioners, and Language Interpreters. These roles vary in terms of clinical scope, and may include communication assistance, community advocacy and clinical procedural work.

When working with an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander healthcare professionals, it is vital that the organisation acknowledges the relationship to country of the individual professional. In many circumstances care is focused towards a particular region or cultural area. It may be inappropriate for a healthcare worker to meet with a certain patient or family based upon geographical, traditional or social factors.

To ensure that you are providing culturally safe and sensitive care, liaise in person with your Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander healthcare professional and discuss the patient case before proceeding. If they are unable to provide support, they may be able to recommend an appropriate service.

Respecting and Involving Family

Healthcare providers should take the time to meet with patients and listen to their stories. With focus on person-centred care, every Australian should be offered the opportunity to receive services in private – or in the company of family and friends – depending on individual preference.

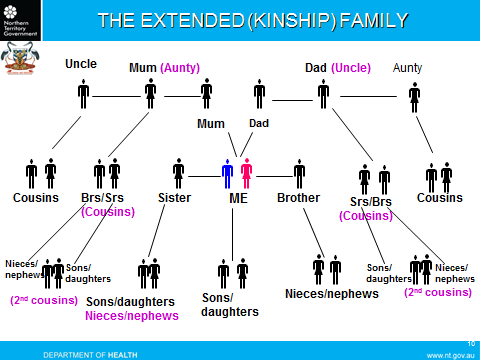

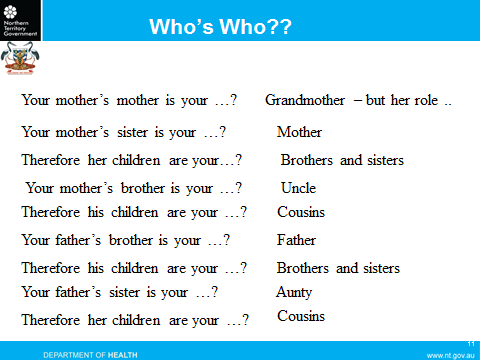

Respect for family is paramount to many cultures, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander traditions in Australia. Integral roles and responsibilities are often shared amongst the extended family, and it is important to understand how social relationships interact with acute and community healthcare. Family roles are not necessarily determined by biological relationships. A biological ‘auntie’ or ‘uncle’ may be referred to as ‘mother’ or ‘father’. A biological ‘cousin’ may be referred to as ‘brother’ or ‘sister’. A biological ‘granddaughter’ or ‘niece’ may be referred to as ‘daughter’.

The acknowledgement of family roles varies between regions and cultural traditions. In some traditions the roles are determined by matriarchal or patriarchal lineage. In other cultures the roles are defined through social relationships. Understanding family roles is essential when identifying an appropriate next of kin – this may not be a spouse or immediate family member, but alternatively, an extended family member or community elder.

To ensure that your patients are treated with respect, you should meet with the individual person and ask if you can listen to their family story. You may be able to ask whom they would like to help make decisions, and who they would like to be present when receiving healthcare information.

It is important to consider that medical decisions may need to be made in the presence of multiple family members, rather than one next-of-kin – particularly if the patient is a young child. Family-assisted treatments may also be the responsibility of an extended family member, rather than an immediate next-of-kin. For example: It may be culturally inappropriate for a biological mother to administer antibiotics to her young daughter with bronchiectasis, as this may be the responsibility of a biological auntie or grandmother.

The acknowledgement of family roles varies between regions and cultural traditions. In some traditions the roles are determined by matriarchal or patriarchal lineage. In other cultures the roles are defined through social relationships. Understanding family roles is essential when identifying an appropriate next of kin – this may not be a spouse or immediate family member, but alternatively, an extended family member or community elder.

To ensure that your patients are treated with respect, you should meet with the individual person and ask if you can listen to their family story. You may be able to ask whom they would like to help make decisions, and who they would like to be present when receiving healthcare information.

It is important to consider that medical decisions may need to be made in the presence of multiple family members, rather than one next-of-kin – particularly if the patient is a young child. Family-assisted treatments may also be the responsibility of an extended family member, rather than an immediate next-of-kin. For example: It may be culturally inappropriate for a biological mother to administer antibiotics to her young daughter with bronchiectasis, as this may be the responsibility of a biological auntie or grandmother.

Professional Relationships

Arrange a time to meet with your patient, their family and support team which may include an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander healthcare professional. It is important to establish open communication for shared listening and knowledge, where the patient has adequate time to tell their story.

In some cases it may be most appropriate to set up multiple sessions just to talk through a plan, without completing any procedures. In other cases a person may wish to minimise contact with their healthcare service. Focus on patient-centred care will enable respectful interactions, recognising the needs of the individual and their community.

Professional Body Language, Contact, and Communication

Expectations surrounding respectful social engagement vary significantly across Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. To ensure conduct is respectful, healthcare professionals are encouraged to read local resources, meet with cultural advisors and learn from community elders. There are key aspects of social interaction where respectful recognition of culture will promote and preserve patient safety.

Understanding Shame:

You may hear patients, families, elders or healthcare professionals refer to the concept of ‘shame’. This is not purely a feeling arising from guilt or disgrace, as would often be noted in European cultural and language interpretation. As described by Morgan, Slade and Morgan (1997), shame may be experienced by social isolation, in conflict to the social and spiritual expectations of community – “It is a powerful emotion resulting from the loss of extended self, and it profoundly affects Aboriginal health and healthcare outcomes”.

People might feel shame for receiving personal attention, being in hospital, experiencing pain, taking medications, or missing important family events. People might also feel shame if they do not understand the information being presented to them, and may reply ‘yes’ or ‘I am alright’ to avoid attention.

It is important that health providers take responsibility for patient comfort, and engage with family and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healthcare Professionals to ensure that patients are supported during healthcare interactions.

Eye contact:

Avoiding eye contact is a sign of respect in many cultures. In other circumstances averting eye gaze may signal to a person that the topic of conversation is sensitive or significant. You are encouraged to meet with your Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander Healthcare Professional to learn of local traditions and expectations.

When establishing a professional relationship, introduce yourself whilst looking towards the patient and their family. If you are met with direct eye contact, you may be able to offer the same in return. If gaze is averted, a person is likely offering respect – acknowledgement through the aversion of your own gaze is an important action that will create a safe and open environment for the patient.

Many languages of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander origin place significant emphasis on hand gestures and postural stance. You are encouraged to meet with your local Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander Healthcare Professional to learn of essential body signals that may demonstrate respect or cause offence. This includes your overall body position in relation to the person you are meeting with.

Avoid postures that may create a power dynamic over a person or their family. If you are meeting at a patient’s bedside, it may be most respectful to sit on a chair next to the bed, looking in the same direction as the patient. If you are meeting in the community, you may need to ask permission to stand or sit with the family. Through genuine interest and learning in the local culture, you are more likely to provide culturally safe and sensitive care that demonstrates insight and respect.

Optimise the accessibility of information

Explain the procedure to the patient

Ensure privacy from, or inclusion of relevant family members

Gain consent as would be expected in any situation of patient-professional interaction

Language & Reading Skills:

Communication:

As languages mould together there are often discrepancies or differences in meaning that can either deliver a sense of respect, or result in social offence. Again, it is important to meet with your local team to learn of expectations specific to the region, culture or connection to country.

The following common examples may offer insight:

Cheeky – may refer to a person who has behaved with deliberate and harmful disrespect, or an amusing and relatively innocent sense of irreverence

Deadly – may refer to something that is excellent or great, a fatal instrument, or an action resulting in death

Finishing up – may refer to the end of a set time frame such as a medical appointment, or may indicate that a person is nearing end of life

Through meaningful learning a healthcare professional can encompass respectful elements of culture in their daily practice. For example: a Pitjantjatjara Aboriginal woman may refer kindly to a younger, female Caucasian health professional as kungka – meaning woman. However, it may be appropriate in response for that health professional to refer to her patient as minyma – a mature and respected woman.

Also be mindful of your vocal volume and length of conversation. In many cultures it is respectful to discuss sensitive or significant issues in a whisper or lower vocal volume. Silence forms an integral part of conversation in many languages, and it is important to allow for breaks in discussion, particularly if you have just asked a question. Allow the patient and their family time to respond in a way that respects culturally sensitive social interaction.

In many languages of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander origin, words for ‘please’ and ‘thank you’ do not exist. This is because there is an expectation that if you are speaking with someone, you should always meet him or her with respect.

It is important that health providers adjust their own expectations and recognise that conversation should always be maintained with respect, without necessarily relying on certain words or phrases. It is disrespectful to suggest that a patient should say ‘please’ or ‘thank you’, if they are requesting help from a staff member.